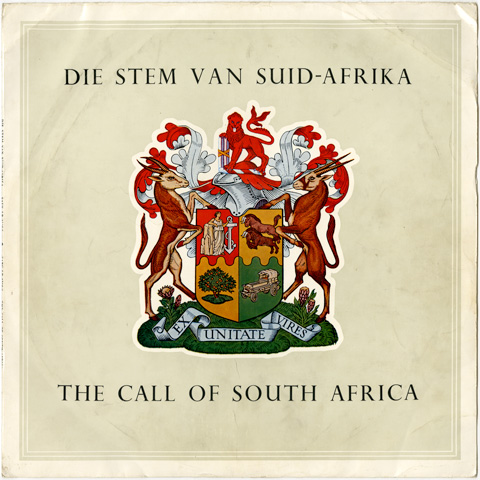

LINER NOTESTHE CALL OF SOUTH AFRICA C. J. LANGENHOVEN wrote the words of Die Stem van Suid-Afrika in 1918. Originally the poem consisted of only three verses, but at the suggestion of various people, the poet added the final verse. The English version, compiled from various individual translations, was officially approved by the Government in 1957. M. L. DE VILLIERS set the poem to music in 1921. In 1936 the Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereniginge chose this setting as the national anthem. In 1957 the Prime Minister declared it the only official national anthem of South Africa. The song was orchestrated for this recording by Hubert du Plessis. ARTISTS Cuts 1-4 (Choral Singing) Combined choir consisting of the ASAF Choir (Chorus master: J. B. Z. Keet) and the Cantare Male Voice Choir (Chorus master : Pierre Malan) with the SABC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Anton Hartman. Cuts 5- 6 (Orchestral) The SABC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Anton Hartman. Cut 7 (Reading) Philip Burgers. Cuts 8-9 The Band of the South African Air Force directed by Captain J. E. Koops van't Jagt. THE CALL OF SOUTH AFRICA Ringing out from our blue heavens, from our deep seas breaking round; Over everlasting mountains where the echoing crags resound; From our plains where creaking waggons cut their trails into the earth Calls the spirit of our Country, of the land that gave us birth. At thy call we shall not falter, firm and steadfast we shall stand, At thy will to live or perish, O South Africa, dear land. In our body and our spirit, in our inmost heart held fast; In the promise of our future and the glory of our past; In our will, our work, our striving, from the cradle to the grave There's no land that shares our loving, and no bond that can enslave. Thou hast borne us and we know thee. May our deeds to all proclaim Our enduring love and service to thy honour and thy name. In the golden warmth of summer, in the chill of winter's air, In the surging life of springtime, in the autumn of despair; When the wedding bells are chiming or when those we love depart, Thou dost know us for thy children and dost take us to thy heart. Loudly peals the answering chorus: We are thine, and we shall stand, Be it life or death, to answer to thy call, beloved land. In Thy power, Almighty, trusting, did our fathers build of old; Strengthen then, O Lord, their children to defend, to love, to hold - That the heritage they gave us for our children yet may be: Bondsmen only to the Highest and before the whole world free. As our fathers trusted humbly, teach us, Lord, to trust Thee still : Guard our land and guide our people in Thy way to do Thy will. Manufactured by the South African Broadcasting Corporation for the official sole distributors the Suid-Afrikaanse Akademie vir Wetenskap en Kuns Engelenburg House, Hamilton Street, Pretoria (SABC LP 1735/6) COPYRIGHT RESERVED DIE STEM VAN SUID-AFRIKA C. J. LANGENHOVEN het die woorde van Die Stem van Suid-Afrika in 1918 geskryf. Dit bet eers net uit drie verse bestaan, maar op voorstel van verskeie persone bet hy die slotvers bygedig. M. L. DE VILLIERS het in 1921 die woorde getoonset. In 1936 het die Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereniginge hierdie toonsetting as ons volkslied aangewys. In 1957 is Die Stem deur die Eerste Minister tot enigste amptelike volkslied van Suid-Afrika verklaar. Die lied is vir hierdie opname geinstrumenteer deur Hubert du Plessis. KUNSTENAARS Bane 1-4 (Koorsang) Gekombineerde koor, bestaande uit die ASAF-koor (koormeester: J. B. Z. Keet) en die Cantare-mannekoor (koormeester: Pierre Malan) met die Simfonie-orkes van die SAUK onder Ieiding van Anton Hartman. Bane 5-6 (Orkes) Die Simfonie-orkes van die SAUK onder Ieiding van Anton Hartman. Baan 7 (Voordrag) Jan Schutte. Bane 8-9 Die Suid-Afrikaanse Lugmagorkes onder Ieiding van kapt. J. E. Koops van't Jagt. DIE STEM VAN SUID-AFRIKA Uit die blou van onse hemel, uit die diepte van ons see, Oor ons ewige gebergtes waar die kranse antwoord gee, Deur ons ver-verlate vlaktes met die kreun van ossewa - Ruis die stem van ons geliefde, van ons land Suid-Afrika. Ons sal antwoord op jou roepstem, ons sal offer wat jy vra: Ons sal lewe, ons sal sterwe - ons vir jou, Suid-Afrika. In die merg van ons gebeente, in ons hart en siel en gees, In ons roem op ons verlede, in ons hoop op wat sal wees, In ons wil en werk en wandel, van ons wieg tot aan ons graf - Dee! geen ander land ons Iiefde, trek geen ander trou ons af. Vaderland! ons sal die adel van jou naam met ere dra: Waar en trou as Afrikaners - kinders van Suid-Afrika. In die songloed van ons somer, in ons winternag se kou, In die lente van ons liefde, in die Ianfer van ons rou, By die klink van huw'liks-klokkies, by die kluitklap op die kis - Streel jou stem ons nooit verniet nie, weet jy waar jou kinders is. Op jou roep se ons nooit nee nie, se ons altyd, altyd ja: Om te lewe, om te sterwe - ja, ons kom, Suid-Afrika. Op U Almag vas vertrouend het ons vadere gebou: Skenk ook ons die krag, o Here! om te handhaaf en te hou - Dat die erwe van ons vaad're vir ons kinders erwe bly: Knegte van die Allerhoogste, teen die hele wereld vry. Soos ons vadere vertrou het, leer ook ons vertrou, o Heer - Met ons land en met ons nasie sal dit wei wees, God regeer. Vervaardig deur die Suid-Afrikaanse Uitsaaikorporasie vir die amptelike alleennverspreiders die Suid-Afrikaanse Akademie vir Wetenskap en Kuns Engelenburghuis, Hamiltonstraat, Pretoria (SAUK LP 1735/6} KOPIEREG VOORBEHOU ADDITIONAL NOTES THE SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL ANTHEM: A HISTORY ON RECORD (extract) By Siemon Allen This text is extracted from an article on the early recordings of the South African National Anthem. The full version can be viewed at the Flaint blog. STANZA 3 “Die Stem” in Afrikaans Uit die blou van onse hemel, Uit die diepte van ons see, Oor ons ewige gebergtes, Waar die kranse antwoord gee, Out of the blue of our heavens Out of the depths of our seas Over our everlasting mountains Where the echoing crags resound104 Cornelis Jacob Langenhoven, an Afrikaans poet wrote the Die Stem, a patriotic poem with three verses in May of 1918. Born on a farm near Ladismith in the Klein Karoo in 1873, he was an educator, solicitor and the editor of a local Dutch newspaper. At that time English and Dutch were the two ‘official’ languages of South Africa while, for many, Afrikaans was simply viewed as a creolized language of convenience and often derogatively referred to as “kitchen-Dutch”. Langenhoven was a proud and ardent supporter of Afrikaans and wrote extensively in support for it to be accepted in an official capacity. He is quoted as having said: “If Dutch is our Language, we must speak it, if Afrikaans is our Language, we must write it”.105 Afrikaans was officially adopted alongside English as the national language of South Africa in 1925. By some accounts, Langenhoven had composed music for his poem, but critics did not entirely approve of the version and so a competition, sponsored by the newly formed Cape Town newspaper, Die Burger, was organised in 1919. Interestingly the founding editor of that paper, D.F. Malan, would become South Africa’s Prime Minister under the National Party when they took power in 1948. Finally the poem was set to music composed by Marthinus Lourens de Villiers and completed on May 31, 1920,106 the tenth anniversary of the formation of the Union of South Africa. Though most accounts have the final date for the composition as 1921. De Villiers, was born in Paarl in the Cape in 1885, three years before his parents would open a music institute in Wellington. His mother, possibly of English heritage, taught him piano and his father, the organ, violin and harmony. He would subsequently also play clarinet in his father’s brass band. De Villiers’s was a composer, but also a pastor and educator. Seeing the destruction of the the Anglo-Boer war left him with a deep desire to identify with his Afrikaner roots and he, until his death in 1977, remained “a pro-Afrikaner volksman”.107 In a 1975 interview De Villiers said that he had composed the music while living in Simontowns, a village on the False Bay side of the Cape Peninsula. He was looking out the window one day watching the waves crash on the beach with a backdrop of the Cape mountains and a clear blue sky: “Net daar het ek die musiek vir Uit die blou van onse Hemel, uit die diepte van ons see, in my voel opwelm en dit dadelik neergeskryf.”108 As mentioned earlier, Langenhoven’s poem originally had only three verses, but a fourth verse was added, by some accounts at the request of the government, to bolster a religious theme. It is not clear to me at what point in the development of the anthem this occurred. The first recording of the future anthem took place in London in 1926 on the Zonophone label and was made by Betty Steyn. The Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurverenigings (FAK) or Federation of Afrikaans Cultural Societies was formed in Bloemfontein in 1929 with the main objective of promoting Afrikaans with a co-ordinated and constructive agenda.114 The organisation also had the goal of reaching a consensus amongst Afrikaners on an anthem in Afrikaans that could be sung side-by-side with God Save the King. The Union of South Africa, then under the dominion of the British Empire, had adopted this anthem with its formation in 1910. In 1936 the FAK finally and unanimously accepted the poem by Langenhoven set to the music of De Villiers as the Afrikaans national anthem.115 It is not clear to me when Die Stem was officially accepted by the government to be played alongside God Save the Queen though it is possible that this had already been taking place since the anthem was first publicly performed in 1928. Die Stem van Suid-Afrika / The Call of South Africa Conducted by J.B.Z. Keet, Pierre Malan and Anton Hartman respectively SABC Transcription Service, LT 1735/6 The Boer War between colonial England and the two Boer republics ended in 1902 and subsequently in 1910 the Union of South Africa was formed as a dominion of the British Empire. In the 1920s, a compromise between Afrikaner Nationalists on one side, and the pro-British English-speaking population on the other — both white — was for the country to have two flags and two anthems: the Union Flag flown side by side with the Union Jack and Die Stem van Suid-Afrika sung together with God Save the King (or Queen). The role played by Eban Dönges in the eventual adoption of Die Stem van Suid-Afrika as the only official national anthem is quite interesting as is revealed in Anton Ettiene Bekker’s biography.120 Dönges was acting Prime Minister of South Africa for eight days after the assassination of Hendrik Verwoerd in September of 1966, but was subsequently replaced by B.J. Vorster. He was then elected State President in June of 1967, but before taking office fell into a coma after having a stroke, and eventually died in January 1968.121 When the National Party came into power in 1948, beyond implementing grand-apartheid, the Afrikaner nationalists also had an agenda of transforming the Union into a Republic and declaring independence from Britain by leaving the British Commonwealth. Part of the goal was to figure out a strategy of stripping the country of its British colonial symbols. Dönges, joined D.F. Malan’s cabinet as the Minister of the Interior in June of 1948. Sixteen months later in September of 1949, the Afrikaanse Taal en Kutuuvereniging (ATKV) or Afrikaans Language and Culture Organisation wrote to Dönges stating that in order to establish national unity, that Die Stem van Suid-Afrika should be declared the only national anthem, and a version should be translated into English. In September 1950, Donges established a committee, chaired by H.A Fagan, to work on a legitimate translation.122 Dönges as Bekker points out was quite enthusiastic about the whole project and even translated some lines of the anthem himself: “‘n Aanduiding van hoe entoesiasties Dönges was, is die veit dat hy self sy hand gewaag het aan die vertaling van sommige strofes en ook veranderinge aangebring het aan van die voorstelle wat ontvang is en later as “The Call of South Africa” die lig gesien het”.123 Subsequently the English translation became known as “The Call of South Africa” and was first published in 1952 and also accepted for official use. But as the matter was still quite controversial, both the Union Jack and God Save the Queen were also still officially used. Moreover both anthems continued to be played after various non-official events, such as at the close of radio broadcasts, or at the end of films in theatres. All the while the Nationalists continued to advocate a position of one flag, one anthem as the only path to achieve comprehensive national unity. In February 1954 a National Party MP, J.P. Basson submitted a motion to the assembly calling for a single flag and anthem. Within two weeks the management of African Consolidated Theatres dropped the British anthem from the close of screenings. Support for the elimination of the dual anthem reached a crossroad when two conservative English-speaking members of Parliament, Arthur Barlow and Frank Wearing, advocated for the single flag, single anthem policy, in March 1956, with Die Stem van Suid-Africa as the only national anthem.124 Interestingly, as Bekker reveals, the debates that followed in the House of Assembly proved to be quite heated. For example, Douglas Mitchell, a United Party MP, rejected the motion on account that it bred division, but also noted that there was an additional anthem being sung by millions of black South Africans: Nkosi Sikelel iAfrika. “Die Verenigde Party se Douglas Mitchell (Natalse Suidkus) het die mosie verwerp omdat dit 'n sensitiewe saak was wa verdeeldheid aangewakker het. Hy het daarop gewys dat daar nog 'n volkslied - Nkosi Sikele iAfrika - is wat deur miljoene swartes in die Unie gesing is.”125 The motion at that time however was tabled. But support both in the Afrikaans and surprisingly in the English press for the single flag, single anthem policy continued. In March 1957 Barlow, the conservative English-speaking MP, this time submitted a private bill to Parliament calling for the Union flag to be adopted. Dönges, as Bekker continues, suggested that a single flag by implication also implies a single anthem, though the anthem did not require a legislative amendment. Thus it was left to Prime Minister J.G. Strijdom, to declare in parliament on May 2nd 1957 that Die Stem van Suid-Afrika would be the only national anthem of the country.126 The controversy was felt worldwide within the British Commonwealth and made the front pages of papers like the Ottawa Citizen. Dönges, the newspaper reported, had to roll back Strijdom’s statement somewhat by saying that God Save the Queen would still be played at official functions where appropriate.127 The British anthem though from then on was dropped. South Africa would eventually leave the Commonwealth and become a Republic on May 31st, 1961. The government sought to claim the copyright of Die Stem van Suid Afrika from the estate of Langenhoven and officially acquired the rights to the poem in the Copyright Act of 1959.128 View a PDF of that document here. STANZA 4 “The Call” in English Sounds the call to come together, And united we shall stand, Let us live and strive for freedom In South Africa our land. A direct translation of the Die Stem van Suid-Afrika in English is “the voice of South Africa”, but the official English version was always known as The Call of South Africa which had been constructed from various translations and set to the same music composed by M.L. De Villiers. On May 2, 1957, Die Stem was unanimously accepted by the then South African parliament as the only official national anthem of South Africa with The Call, the English translation, being approved on November 26th that same year.129 It is interesting to note that the words “the call” are used in the first line of the only stanza of the new anthem that has been severely modified from its original version. Below is the opening stanza of the original 1957 version of The Call in English. The first two lines represent the Afrikaans third stanza (or Die Stem) in the current version of the anthem. The fourth English stanza of the current version is derived in part from the last three lines of the original English version. Of course the new lyrics have been heavily adapted but there are a number of themes and words (that I have underlined below) that are common to both new and old versions. Ringing out from our blue heavens, from our deep seas breaking round; Over everlasting mountains where the echoing crags resound; From our plains where creaking wagons cut their trails into the earth - Calls the spirit of our country, of the land that gave us birth. At thy call we shall not falter, firm and steadfast we shall stand, At thy will to live or perish, O South Africa, dear land.130 To my knowledge, the first recording of the original English version of The Call was issued on an SABC transcription disc in what I am assuming was 1960. This assumption is based on the fact that the back cover carries the red Union Festival Emblem of the fiftieth anniversary of the Union of South African, which took place in May 1960. The recording may have occurred earlier somewhere between 1957 and 1960. Transcription discs were for the most part issued in limited pressings with generic covers and distributed to radio stations around South Africa and internationally. This particular disc is unique in that it came with a specially designed cover and detailed liner notes and may have been issued as a collectable for the general public. What was to become a standard procedure in ‘white’ South Africa, the disc was issued completely bilingually in English and Afrikaans. Side A in Afrikaans was exactly the same as side B in English and both sides featured four versions of the anthem: the full version sung with orchestra; an orchestral rendition alone; unaccompanied readings of the anthem by Jan Schutte in Afrikaans and Philip Burgers in English; and then an identical military version played by the Band of the South African Air Force directed by Captain J. E. Koops van’t Jagt. The only difference between the two sides (other than the obvious language differences) can be found in the liner notes. The English text includes this sentence: “The English version, compiled from various individual translations, was officially approved by the Government in 1957” while the Afrikaans translation omits this detail.131 Perhaps this omission reflects the continuation of long-felt acrimony between the two so-called ‘white’ language and therefore cultural groups in South Africa that had existed since, at least, the Boer Wars and, perhaps to a lesser extent, continues today. What is implied in this phrasing in the liner notes is this: explaining in Afrikaans where the English translation came from needs no explanation, because the Afrikaans version is the ‘only version’ and ‘derivatives’ need no explanation. Having said that, I seldom recall singing the English version of the anthem as a youth growing up in Durban in the 1970s and 80s. Durban of course, at that time, was considered to be the most ‘English’ of South African cities. As I read the 1957 English lyrics, they seem quite unfamiliar to me, though mind you anything beyond the first stanza of the Afrikaans version seems for me to be ‘lost in the grass’. Perhaps for that reason it was the English lyrics that were open to be radically altered in the new version of the anthem without the fear of too much recrimination. |

VARIOUS ARTISTS

|

||||||||||

TRACK LISTING

|

||||||||||

ARTISTS

| ||||||||||

NOTESFor more information about this record and the anthem, read my full article, The South African National Anthem: a history on record at the Flatint blog. |

||||||||||