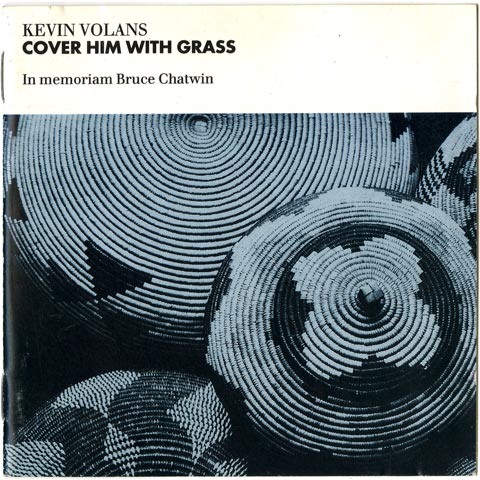

LINER NOTESCOVER HIM WITH GRASS In memoriam Bruce Chatwin The initial impulse for writing these pieces was a reconciliation of African and European aesthetics. They are not minimalist. When I wrote them I was frustrated both with the bland mechanism of repeat-pattern music and with serial technique. I wanted to move away from a conceptualist approach to composition. Traditional African music has an existential quality which attracted me. It is essentially a music of being not becoming. It does not aim at transporting the listener, but reinforces and intensifies the here and now. The music is not conceptualised in any way. I took the liberty of approaching European music from the point of view of an African. This learning process led me to more flexible solutions. Shortly after writing these pieces I realised that style is not a way to begin a composition. Style is a red-herring; it can stand in the way of both the composer and the listener. MBIRA 1980 two harpsichords and rattles This piece is based on the traditional Shona tune Nyamaropa from Zimbabwe. It is played in an African tuning of roughly seven equal steps to the octave. Mbira is the generic name of a popular African instrument with a set of plucked keys, a soundboard and resonator, thought to have been invented between 1000 and 2000 years ago. My piece Mbira began as a simple transciption for harpsichords of Mbira Dza Vadzimu music. The timbre of 17th and 18th century harpsichords - their individuality, the way each instrument 'speaks' - as well as the fact that they are easily re-tuned, made them highly suitable for this music. Later I added my own patterns composed in traditional Shona style as well as a non-traditional coda. All of the 48-note patterns are based on the same cyclic 'chord' progression of 12 fifths. The technique of performing this music involves improvisation around the basic patterns, in which the chord progression is strictly adhered to, but left-hand as well as right-hand patterns are exchanged freely at any point during the cycle. The number of repetitions of the patterns is at the discretion of the players. An important feature of the music is the interlocking of the players, in which one player's pattern begins one note later than the other. So each player (including the rattle player) has an equal and independent down-beat. This means that one combined pattern can often be heard in two distinctly different ways, rather like the shifting focus in some optical illusions. There is no parallel for this in Western music. I hoped that by approaching Mbira music in this direct way I would be able to learn something about composition without proportioning, and escape a little from that distinctly Western anxiety which demands timed change. I also hoped it might cast some new light on traditional Western instruments. WHITE MAN SLEEPS 1982 two harpsichords, viola da gamba, percussion In 1982 Adrian Jack planned an installation of my tape works as well as live performances of my more African pieces in his MusICA concert series at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (London). He asked me to write a piece to complement Mbira and Matepe. This posed a daunting problem. The tuning system of the other pieces was specific to Mbira-style music, and I wanted to write something quite different. I realised I could add viola da gamba to the ensemble because its movable frets could cope with the tuning. This would also give me an opportunity of working with my friend Margriet Tindemans. A long search for music appropriate to the tuning ensued. In the end I drew from Tswana and nyanga panpipe music, from San bow music, and from Basotho lesiba music and concertina style, to which I added my own invented folklore. My approach was anything but purist - the music is Altered, slowed down by a few 'time-octaves', cast into non-African metres (like the 13-beat pattern of the last dance) and re-distributed between the players in several ways. I also used interlocking techniques where they were absent in the original models and vice versa. This treatment now seems to me to be unacceptably Germanic, but at the time I was still very much a Cologne composer. I feel that the piece has more to do with European music in the 1980's than anything else. The title White Man Sleeps comes from a moment in nyanga panpipe music where the performers leave off playing their loud pipes for a few cycles and dance only to the sound of their ankle rattles, to let the white landowner sleep - for a minute or two. SHE WHO SLEEPS WITH A SMALL BLANKET 1985 percussion solo: four bongos, two congas, bass drum, marimba In concerts of music involving 'talking drums' we are often told that the drums are used to relay messages. Why, I wonder, are we told this? Should we listen to the music differently, hoping to understand some message? Or are we to try to appreciate the sounds as absolute music, overlooking any important news they may be conveying? And what of the performer energetically sending out messages which he knows are not being understood? This disconcerting image gave the initial impetus for She Who Sleeps with a Small Blanket, although the piece itself has nothing to do with African drumming. After some debate we decided to use the recording of this brilliant live performance. It is rarely possible to capture such a degree of tension and energy in a studio situation. The dynamic range of the piece is extreme. Play it at as high a level as you dare, in a quiet environment. The beginning should be the very loud, the marimba solo at the end will be barely audible. This piece is dedicated to Robyn Schulkowsky. WHITE MAN SLEEPS 1986 for string quartet It was again a request from Adrian Jack that prompted this piece. He asked me to rework White Man Sleeps for the Kronos quartet for a performance at the ICA. I resisted the idea at first, especially as the African tuning of the original would have to be dropped. It occurred to me, however, that the western tuning (equal temperament) would mask the source material and make my intensions clearer. I began work. After the first performance I changed the order of the movements, placing the last dance, which seemed to me to be the weakest, first. Thus the piece quietens down and becomes more intimate as it progresses. This became Bruce Chatwin's favourite piece of music, and he played it incessantly during the last few months of his life. Excerpt from a profile of Kevin Volans by Bruce Chatwin One morning last February, during a very bad bout of malaria, the post brought a most intriguing letter from a South African composer I had never heard of: Kevin Volans. 'I have been meaning to write to you for some time, but the temptation of adding some presumptuous invitation... to come with me on a recording trip in Lesotho... held me back.' His titles were wonderful: White Man Sleeps, She Who Sleeps with a Small Blanket, Cover Him with Grass, Studies in Zulu History, Kneeling Dance, Leaping Dance, Hunting: Gathering. I was too feverish to play Volans' tape at once but finally summoned the strength to put it on the tape deck. It was a dazzling, frosty day and my bedroom, with its white walls and white Venetian blinds, was slatted with sunlight. I was boiling hot. I lay back and could not believe my ears. I was listening to White Man Sleeps, scored for two harpsichords, viola da gamba and percussion. It was a music I had never heard before or could have imagined. It derived from nothing and no one. It had arrived. It was free and alive. I heard the sounds of thorn-scrub Africa, the insects and the swish of wind through grass. But there was nothing that would have been foreign to Debussy or Ravel. I called him up in Belfast where he was Composer-in-Residence at Queen's University. Mine was the first call on his new answering-machine. Within a very few days he was at my bedside. I had a friend for life. Kevin comes from Pietermaritzburg, the most English city in South Africa, and is thirty-eight years old. His parents owned a dry-cleaning business. When he was ten his mother bought a piano. By the time he was fourteen he was playing Liszt's Piano Concertos and wanted to be a concert pianist. He was terrorised by the other boys on the school bus, and would walk home in temperatures of 105°, in a black flannel blazer, grey flannel trousers, spit-and-polish shoes and a boater hat. On the way he passed Africans sheltering under the trees, hearing the people's song, guitar music and work rhythms. He went to Johannesburg to study Western music without yet being aware that he loved the sounds of Africa. He came to Europe in 1973 and studied with Karlheinz Stockhausen, later becoming his teaching assistant. He studied piano with Aloys Rontarsky and music theatre with Mauricio Ragel. He began to realize that what distinguished African music from European (except perhaps for early music like that of Hildegard of Bingen) was its unawareness of proportion. African music is not deliberately asymmetric, it has no precise proportions: patterns are created by addition, not subdivision. In many cases repetition is not perceived. The music ends as abruptly as it begins, like bird song. No rhythm is arrived at by calculation - Stockhausen calculates everything. Arriving fresh from a field trip in the mountains of Lesotho, Kevin made straight for a Cologne premiere by the German composer and was struck by the conviction that the language of serialism was dead. Western music was always architectural: he wanted a music in which the roof floated free. Kevin had two colleagues, Walter Zimmermann, the son of a Nuremburg baker, and Clarence Barlow, who was born in Calcutta. They decided to return home and investigate the relation of music to its geographical source. This was not shopping around the world of ethnomusicology. Zimmermann produced what he called Lokale Musik with the implication that the local was the universal: he composed a series of works that would define aspects of his tradition. One of these was an orchestral work in which he mapped features of his native landscape onto the orchestration of some two hundred rustic waltzes (Landlertopographien). Clarence Barlow came back from Calcutta with a twenty-four-hour cycle of street sounds, and an analysis of harmonic and rhythmic consonance and dissonance in Indian music. Kevin made several recording trips to Southern Africa. He began with street-music and immediately realized it was far more interesting than any ideas about it. Zulu guitar music is not only used as an accompaniment to long walking journeys, but as a means of making friends and working out social tensions: in what appears to be ritualized aggression, Zulu guitar players engage in a musical substitute for stick fighting. The two players will meet and one of them will say, 'You stab first'. The songs always include elaborate introductory flourishes and praise-poetry recited at high speed over the guitar ostinato. 'Studies in Zulu History' began as an attempt to record the great Afrikaner festival at the church where King Dingaan killed the Boer leader, Piet Retief, a founder of Pietermaritzburg. On a day known as the Day of the Covenant a Boer massacre of the Zulus is remembered annually. Kevin saw the faces of the congregation and got cold feet. It was midday, he wandered off into the veld and recorded the prehistoric sounds of insects, the heat rising and an occasional bird. He took the tape back to Europe and spent three years on and off in the Cologne studios making an electronic replica. 'Cover Him with Grass' is derived from Basotho worksounds in which old men split a log, children shout and women sing as they throw chips of stone while road-building. 'KwaZulu Summer Landscape' is an extended composition of natural sounds collected on a return trip. These tape pieces serve as a curtain raiser to a long series of instrumental works which aimed at reconciling African and European aesthetics. Islam tends to introduce new techniques to its converts, Christianity brings new objects. In the predominantly Christian South the musical techniques remain traditional, the instruments imported. Kevin chose to make an inverse assault on European music, bringing new techniques from the South and adapting existing instruments and forms: the harpsichord, the flute, the string quartet. He avoided exotica. On returning from Africa he was bitterly disappointed to discover he was neither African or European. Soon he realized he was free, free to compose whatever he wanted. There is a Sufi saying, 'Freedom is absence of choice.' I believe this to be devotional music of the highest order. For me, Kevin is one of the more inventive composers since Stravinsky. First published in the New York Review of Books and reprinted in Bruce Chatwin's What Am I Doing Here (Jonathan Cape, London 1989) © 1989 the Legal Personal Representatives of C. B. Chatwin Acknowledgements Special thanks to Christopher Ballantine, Elizabeth Chatwin, Robyn Schulkowsky, Paul Simmonds, Margriet Tindemans, Andrew Tracey and the many musicians I met in Lesotho. |

KEVIN VOLANS

|

||||||||||

TRACK LISTING

|

||||||||||

ARTISTS

| ||||||||||

NOTESMbira could be one of my all-time favorite tracks. For more about Kevin Volans visit his website here. |

||||||||||